Dear readers,

You find the Sybarite on tour and in the field. I write this from possibly my favourite bar in all the world, The Last Hurrah in the Parker House in Boston.(That there is a hurricane a-comin' is neither hither nor yon; rest assured that your faithful correspondent will do his best not to fall victim to Irene's very un-eirenic fury.)

The Parker House is America's oldest continuously-operating hotel, albeit the building has changed. It opened in 1855, on the corner of School Street and Tremont Street, and the current, very charming, building dates from the 1920s. It has been a central part of Boston life ever since; Charles Dickens stayed here during his time in the USA, and associated (one would like to think caroused) with luminaries of American literature like Oliver Wendell Holmes and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; John F. Kennedy was a frequent visitor, holding his bachelor party here, announcing his candidacy for Congress in the Press Room, and proposing to Jacqueline Bouvier in Parker's Restaurant (at table 40, since you ask); and, bizarrely, both Ho Chi Minh and Malcolm X worked here, though not at the same time.

The Last Hurrah is the hotel's bar. And what a bar it is. It is named for Edwin O'Connor's fine novel of Boston politics, in which the veteran pol and several-times mayor, Frank Skeffington, commits himself to one last campaign in the city. Although the city in the novel is unnamed, it is quite clearly Boston, and Skeffington is a thinly-veiled portrait of James Michael Curley, the mercurial master of Boston politics for much of the 20th century. The Last Hurrah opened in 1969, in the part of the hotel which had once been the barbershop where Curley used to have his hair cut.

This is a bar in which you can easily imagine shady deals and backstairs negotiations going on. Seats are leather and comfortable, the lights dim as evening comes on, and world-weary and worldy-wise barmen stand behind a fine L-shaped bar. Cigar smoke curling towards the ceiling would fit the place very well, were it not for the strictures of Massachusetts state law. There is a fine range of draught beers, and an impressive cocktail list. He who has not sampled The Last Hurrah's basil gimlet cannot truly be said to have lived; their "perfect" martini is pretty damned good too, an interesting and slightly retro twist on the usual recipe involving both dry and sweet vermouth. Some of the cocktails are a bit too outré for the Sybarite's taste - a Lights Out is Plymouth gin, ginger simple syrup and fresh lime juice topped up with Pilsner Urquell, a Blue Dress is Absolut, blue curaçao, lemon sour and (Heaven help us) 7-Up, and, in a triumph of bonkers-ness, a Last Hurrah martini is Absolut with Bloody Mary and clam juice, served with a garnish of a chilled shrimp. But let a thousand flowers bloom.

There is also a superb range of spirits. 22 bourbons, 15 whiskeys, a dozen tequilas, as many rums and no fewer than 60 scotches. If you can't find something you like in that selection, you need to rethink your priorities. And, as if that was not enough, there are a dozen ports, which can be sampled with different kinds of chocolate.

The food selection is modest, perhaps, but more than satisfactory, majoring on hearty sandwiches (on one of which your intrepid correspondent almost choked last year) and rib-sticking classics. This very evening I had an excellent sirloin tip stew, while my companion feasted on meat loaf with mashed potatoes. Desserts include, of course, the Boston cream pie which is the hotel's contribution to gastronomic Americana.

The clientele is mixed. Many, of course, are hotel guests. A good number are pols from the State House or City Hall, both within metaphorical spitting distance. Some are ladies who lunch, or weary office-workers. And there is a leavening of older men who sit at the bar and peer intently at the ball game on the screens above (remarkably, to one who is not a baseball fan, it is very unobtrusive). But all men and women are equal here.

A final word on the staff. I do find that waiting staff in the US tend to be more professional and more attentive, on average, than back home. Here, they are, perhaps, a mixed bag, but most are fine, and some are very good. But the Palme d'Or goes to Peggy, my waitress this evening and on many evenings past, who may simply be the best waitress I have been tended to by; cheerful, friendly but not intrusive, efficient, watchful and smart.

Et enfin. I probably have not done the place justice. It may not suit everyone. But, a simple plea: if you are ever in Boston, and you appreciate a good drink - of whatever sort - in fine surroundings, drop in. Sit back. Think, and savour. And maybe, just maybe, you may come round to my way of thinking that this is one of the very finest bars in the world. Peggy, another glass of merlot, I think...

Lover of fine things. St Andrews graduate. Gin enthusiast. Sometime Tudor monastic historian and writer on politics, culture and other matters. Views own.

Friday, 26 August 2011

Wednesday, 17 August 2011

Style Icons No. 1: Anthony Eden

Dear readers,

This is the first in a series of occasional columns examining, well, style icons, as the title will suggest to the more observant reader. Suggestions are welcome for future subjects, but don't be surprised if I disagree and disregard them. I'm just like that.

Our first subject is Sir Anthony Eden, later Earl of Avon, probably the most glamorous figure in British politics in the 20th century, and certainly one of the very few for whom style was an integral part of the image. Eden was born into an aristocratic family of County Durham landowners, and, after a "good war" with the King's Royal Rifle Corps - a Military Cross and the distinction of being the British Army's youngest brigade major - then a first-class degree at Oxford's most well-to-do college, Christ Church, he went into politics and was elected to the House of Commons at the age of twenty-six. He would be at the centre of affairs for another quarter-century.

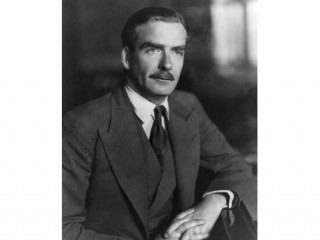

The 1920s, of course, were a decade of great changes in men's fashion. The First World War had a profound effect on clothes, and the frock coats which were all but ubiquitous in the Edwardian era were not often to be seen by the middle of the decade. Instead, lounge suits were in, and Eden was invariably well turned-out. Here he is in his pomp:

Note the peaked lapels on the coat, a little 'racier', somehow, than notched, at least on a lounge suit. Note also the double-breasted waistcoat, also with lapels. (A colleague once said to me, eyeing my suit: "Ah, lapels on a waistcoat. Always saucy." This from a man who had worked in the Diplomatic Service.) Also key to his look was the moustache; to be sure, not an unusual adornment in the 1920s and 1930s, but Eden's was always neatly trimmed and tended. By contrast, Harold Macmillan, his near-contemporary, had a shaggy soup-strainer which never lent him the air of elegance that Eden had.

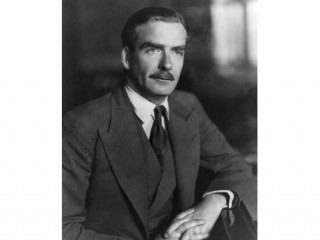

It helped, of course, that Eden was a good-looking man, though there was something feminine about him, both in looks and temperament. Rab Butler described him as "half mad baronet, half beautiful woman", and, while it was an unkind gibe, there was a great deal of truth in it. Here he is at his youthful best.

Again, a double-breasted waistcoat. The white pocket square is a study in carefully-arranged casualness. The hair is perfectly parted and Brylcreemed, and he is every inch the modern and dashing politician. Remember that in the inter-War years his colleagues were men like Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. Against that backdrop, Eden seemed like a creature from a different world.

Of course, the image was part of his political persona. As he emerged as a leading opponent of Chamberlain's policy of appeasement, following his resignation as Foreign Secretary in February 1938, he and his like-minded colleagues were labelled as The Glamour Boys by the Tory Chief Whip, David Margesson; and it seems unlikely that Margesson meant it kindly.

Perhaps Eden's most significant contribution to fashion in the inter-War years was his popularisation of the Homburg, to such an extent that it became known as an 'Anthony Eden hat'. The Homburg was not, of course, new, having been sported extensively by Edward VII. But it became indelibly associated with Eden to the extent that it became his trademark. Here he is carrying it off beautifully:

We might also observe the splendidly-cut overcoat and the casually-swung umbrella. The very picture of a dashing young man in British politics.

Another 1930s trend which Eden helped to foster was the wearing of a pale, often linen, waistcoat with a dark lounge suit. It is, I can say from personal experience, a very pleasing look, though one must be careful and conservative with the choice of shirt and tie. Here Eden pulls it off to perfection:

Again, peaked lapels on the suit, and, of course, a Homburg, worn at a slight angle.

Anthony Eden retained good looks and elegance into late middle age and beyond. By the early 1950s, his reputation was at its height. Foreign Secretary again (for the third time), and Churchill's (often impatient) heir, he brought the Geneva Conference of 1954 to a successful conclusion and was rewarded by HM The Queen with the Order of the Garter. At his second wedding, to Churchill's niece Clarissa, he cut a very dashing figure.

A splendid double-breasted suit, a carnation in the buttonhole, and a flourish of pocket square. Perfect. But he could 'do' casual, too. Observe here the sweater, open-necked shirt and neckerchief, elegant but underplayed, and quite marvellous.

Eden's reputation for style and glamour attracted some criticism. There is a sort of Englishmen who regards care taken over one's appearance with suspicion, and Eden was never short of detractors. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres dismissed him as being "vain as a peacock and [having] all the mannerisms of a petit maître", while Sir Percy Grigg, his Permanent Secretary at the War Office in 1940, described him as a "poor feeble little pansy".

Was Eden vain? My suspicion is not, at least, not in the fully derogatory sense in which the word tends to be used. Certainly, he was careful about his appearance, and was lucky enough to be a first-class clothes horse. He must surely have been conscious of the effect his manner of dress had, and the popularity which it brought him. But my sense is that it was simply second nature to him. It was not an act, in the way in which his successor Harold Macmillan's slight shabbiness and exaggerated old age most definitely was. Of course, it doesn't matter about his intent. The effect is what matters, and the effect was glorious. How many of today's politicians are as glamorous and as renowned for it? Maybe some of them might come across this blog and take a long, hard look at their wardrobes...

This is the first in a series of occasional columns examining, well, style icons, as the title will suggest to the more observant reader. Suggestions are welcome for future subjects, but don't be surprised if I disagree and disregard them. I'm just like that.

Our first subject is Sir Anthony Eden, later Earl of Avon, probably the most glamorous figure in British politics in the 20th century, and certainly one of the very few for whom style was an integral part of the image. Eden was born into an aristocratic family of County Durham landowners, and, after a "good war" with the King's Royal Rifle Corps - a Military Cross and the distinction of being the British Army's youngest brigade major - then a first-class degree at Oxford's most well-to-do college, Christ Church, he went into politics and was elected to the House of Commons at the age of twenty-six. He would be at the centre of affairs for another quarter-century.

The 1920s, of course, were a decade of great changes in men's fashion. The First World War had a profound effect on clothes, and the frock coats which were all but ubiquitous in the Edwardian era were not often to be seen by the middle of the decade. Instead, lounge suits were in, and Eden was invariably well turned-out. Here he is in his pomp:

Note the peaked lapels on the coat, a little 'racier', somehow, than notched, at least on a lounge suit. Note also the double-breasted waistcoat, also with lapels. (A colleague once said to me, eyeing my suit: "Ah, lapels on a waistcoat. Always saucy." This from a man who had worked in the Diplomatic Service.) Also key to his look was the moustache; to be sure, not an unusual adornment in the 1920s and 1930s, but Eden's was always neatly trimmed and tended. By contrast, Harold Macmillan, his near-contemporary, had a shaggy soup-strainer which never lent him the air of elegance that Eden had.

It helped, of course, that Eden was a good-looking man, though there was something feminine about him, both in looks and temperament. Rab Butler described him as "half mad baronet, half beautiful woman", and, while it was an unkind gibe, there was a great deal of truth in it. Here he is at his youthful best.

Again, a double-breasted waistcoat. The white pocket square is a study in carefully-arranged casualness. The hair is perfectly parted and Brylcreemed, and he is every inch the modern and dashing politician. Remember that in the inter-War years his colleagues were men like Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. Against that backdrop, Eden seemed like a creature from a different world.

Of course, the image was part of his political persona. As he emerged as a leading opponent of Chamberlain's policy of appeasement, following his resignation as Foreign Secretary in February 1938, he and his like-minded colleagues were labelled as The Glamour Boys by the Tory Chief Whip, David Margesson; and it seems unlikely that Margesson meant it kindly.

Perhaps Eden's most significant contribution to fashion in the inter-War years was his popularisation of the Homburg, to such an extent that it became known as an 'Anthony Eden hat'. The Homburg was not, of course, new, having been sported extensively by Edward VII. But it became indelibly associated with Eden to the extent that it became his trademark. Here he is carrying it off beautifully:

We might also observe the splendidly-cut overcoat and the casually-swung umbrella. The very picture of a dashing young man in British politics.

Another 1930s trend which Eden helped to foster was the wearing of a pale, often linen, waistcoat with a dark lounge suit. It is, I can say from personal experience, a very pleasing look, though one must be careful and conservative with the choice of shirt and tie. Here Eden pulls it off to perfection:

Again, peaked lapels on the suit, and, of course, a Homburg, worn at a slight angle.

Anthony Eden retained good looks and elegance into late middle age and beyond. By the early 1950s, his reputation was at its height. Foreign Secretary again (for the third time), and Churchill's (often impatient) heir, he brought the Geneva Conference of 1954 to a successful conclusion and was rewarded by HM The Queen with the Order of the Garter. At his second wedding, to Churchill's niece Clarissa, he cut a very dashing figure.

A splendid double-breasted suit, a carnation in the buttonhole, and a flourish of pocket square. Perfect. But he could 'do' casual, too. Observe here the sweater, open-necked shirt and neckerchief, elegant but underplayed, and quite marvellous.

Eden's reputation for style and glamour attracted some criticism. There is a sort of Englishmen who regards care taken over one's appearance with suspicion, and Eden was never short of detractors. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres dismissed him as being "vain as a peacock and [having] all the mannerisms of a petit maître", while Sir Percy Grigg, his Permanent Secretary at the War Office in 1940, described him as a "poor feeble little pansy".

Was Eden vain? My suspicion is not, at least, not in the fully derogatory sense in which the word tends to be used. Certainly, he was careful about his appearance, and was lucky enough to be a first-class clothes horse. He must surely have been conscious of the effect his manner of dress had, and the popularity which it brought him. But my sense is that it was simply second nature to him. It was not an act, in the way in which his successor Harold Macmillan's slight shabbiness and exaggerated old age most definitely was. Of course, it doesn't matter about his intent. The effect is what matters, and the effect was glorious. How many of today's politicians are as glamorous and as renowned for it? Maybe some of them might come across this blog and take a long, hard look at their wardrobes...

Tuesday, 2 August 2011

Review: Skylon

Yesterday afternoon - and what a glorious afternoon it was - found the Sybarite at the Skylon bar in the Royal Festival Hall. It was not my first visit by any means, nor will it be my last; in addition it was a relatively fleeting stop. Nevertheless, it is worth flying the flag for this excellent establishment.

Skylon is named, of course, after the iconic structure of the 1951 Festival of Britain, the vertical 'needle which, so the joke of the time went, was like the British economy, in having no visible means of support. (Interestingly, by which I mean it interests me, the fate of the Skylon is unknown, with one theory having it thrown into the River Lea when the Festival site was dismantled.) But I digress.

Skylon is also a restaurant as well as a cocktail bar, but I have not eaten there, so cannot comment (though the bar snacks are excellent). But what makes the place such an attractive destination to me is the cocktail bar. The range is superb, and the staff give the impression that they know what they are doing. Though I have never needed to do so, I am quite sure that you could go off piste and they would not bat an eyelid. Prices are not cheap; most cocktails are £11.50 and other drinks are of a piece. But I have paid more for worse cocktails and much worse service.

As it was a flying visit, with only time for two drinks, I kept it simple and ordered a martini. The options are agreeably many: vodka or gin, dry or dirty, garnished with an olive, a twist of lemon, lime or orange, or a cocktail onion (which would strictly make it a Gibson, but never mind). I requested a very dry gin martini - it was Tanqueray - with a twist of orange, as I was feeling frivolous and summery. Reader, I would have married it. It was everything a good martini should be, powerful, crisp, clean, refreshing, and with a healthy gin kick. It was no meagre measure and the twist was artfully presented.

My companion opted for an Aviation: Tanqueray 10, Luxardo maraschino, fresh lemon juice, a dash of sugar and violet syrup, shaken and served in a martini glass. It resembled nothing so much as a White Lady, but I am told it was pleasantly cool and refreshing on such a hot day. (Note to self - make a White Lady later. Mmmmmmm.)

In addition to excellent cocktails and good service, there is, of course, the location. We were seated by the window, looking out across the South Bank and the Thames, and, I must add, with a touch of schadenfreude, the poor punters baking in the heat outside, while we were coolly air-conditioned. The staff had pulled the blinds down a little far for my tastes, but then, with all that glass, the place could easily become a hothouse.

So, dear readers. Go to Skylon. If you fancy yourself anything of a cocktail fan, you must go. Even if cocktails aren't your thing (in which case you must be very odd), it is an excellent bar with attentive staff, a fine range of drinks and a lovely atmosphere. It's not cheap, but it should be, at least, an occasional treat.

Skylon is named, of course, after the iconic structure of the 1951 Festival of Britain, the vertical 'needle which, so the joke of the time went, was like the British economy, in having no visible means of support. (Interestingly, by which I mean it interests me, the fate of the Skylon is unknown, with one theory having it thrown into the River Lea when the Festival site was dismantled.) But I digress.

Skylon is also a restaurant as well as a cocktail bar, but I have not eaten there, so cannot comment (though the bar snacks are excellent). But what makes the place such an attractive destination to me is the cocktail bar. The range is superb, and the staff give the impression that they know what they are doing. Though I have never needed to do so, I am quite sure that you could go off piste and they would not bat an eyelid. Prices are not cheap; most cocktails are £11.50 and other drinks are of a piece. But I have paid more for worse cocktails and much worse service.

As it was a flying visit, with only time for two drinks, I kept it simple and ordered a martini. The options are agreeably many: vodka or gin, dry or dirty, garnished with an olive, a twist of lemon, lime or orange, or a cocktail onion (which would strictly make it a Gibson, but never mind). I requested a very dry gin martini - it was Tanqueray - with a twist of orange, as I was feeling frivolous and summery. Reader, I would have married it. It was everything a good martini should be, powerful, crisp, clean, refreshing, and with a healthy gin kick. It was no meagre measure and the twist was artfully presented.

My companion opted for an Aviation: Tanqueray 10, Luxardo maraschino, fresh lemon juice, a dash of sugar and violet syrup, shaken and served in a martini glass. It resembled nothing so much as a White Lady, but I am told it was pleasantly cool and refreshing on such a hot day. (Note to self - make a White Lady later. Mmmmmmm.)

In addition to excellent cocktails and good service, there is, of course, the location. We were seated by the window, looking out across the South Bank and the Thames, and, I must add, with a touch of schadenfreude, the poor punters baking in the heat outside, while we were coolly air-conditioned. The staff had pulled the blinds down a little far for my tastes, but then, with all that glass, the place could easily become a hothouse.

So, dear readers. Go to Skylon. If you fancy yourself anything of a cocktail fan, you must go. Even if cocktails aren't your thing (in which case you must be very odd), it is an excellent bar with attentive staff, a fine range of drinks and a lovely atmosphere. It's not cheap, but it should be, at least, an occasional treat.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)