This is the first in a series of occasional columns examining, well, style icons, as the title will suggest to the more observant reader. Suggestions are welcome for future subjects, but don't be surprised if I disagree and disregard them. I'm just like that.

Our first subject is Sir Anthony Eden, later Earl of Avon, probably the most glamorous figure in British politics in the 20th century, and certainly one of the very few for whom style was an integral part of the image. Eden was born into an aristocratic family of County Durham landowners, and, after a "good war" with the King's Royal Rifle Corps - a Military Cross and the distinction of being the British Army's youngest brigade major - then a first-class degree at Oxford's most well-to-do college, Christ Church, he went into politics and was elected to the House of Commons at the age of twenty-six. He would be at the centre of affairs for another quarter-century.

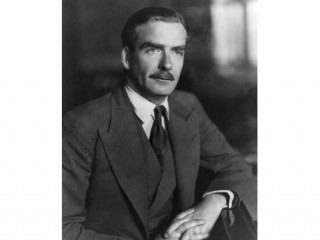

The 1920s, of course, were a decade of great changes in men's fashion. The First World War had a profound effect on clothes, and the frock coats which were all but ubiquitous in the Edwardian era were not often to be seen by the middle of the decade. Instead, lounge suits were in, and Eden was invariably well turned-out. Here he is in his pomp:

Note the peaked lapels on the coat, a little 'racier', somehow, than notched, at least on a lounge suit. Note also the double-breasted waistcoat, also with lapels. (A colleague once said to me, eyeing my suit: "Ah, lapels on a waistcoat. Always saucy." This from a man who had worked in the Diplomatic Service.) Also key to his look was the moustache; to be sure, not an unusual adornment in the 1920s and 1930s, but Eden's was always neatly trimmed and tended. By contrast, Harold Macmillan, his near-contemporary, had a shaggy soup-strainer which never lent him the air of elegance that Eden had.

It helped, of course, that Eden was a good-looking man, though there was something feminine about him, both in looks and temperament. Rab Butler described him as "half mad baronet, half beautiful woman", and, while it was an unkind gibe, there was a great deal of truth in it. Here he is at his youthful best.

Again, a double-breasted waistcoat. The white pocket square is a study in carefully-arranged casualness. The hair is perfectly parted and Brylcreemed, and he is every inch the modern and dashing politician. Remember that in the inter-War years his colleagues were men like Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. Against that backdrop, Eden seemed like a creature from a different world.

Of course, the image was part of his political persona. As he emerged as a leading opponent of Chamberlain's policy of appeasement, following his resignation as Foreign Secretary in February 1938, he and his like-minded colleagues were labelled as The Glamour Boys by the Tory Chief Whip, David Margesson; and it seems unlikely that Margesson meant it kindly.

Perhaps Eden's most significant contribution to fashion in the inter-War years was his popularisation of the Homburg, to such an extent that it became known as an 'Anthony Eden hat'. The Homburg was not, of course, new, having been sported extensively by Edward VII. But it became indelibly associated with Eden to the extent that it became his trademark. Here he is carrying it off beautifully:

We might also observe the splendidly-cut overcoat and the casually-swung umbrella. The very picture of a dashing young man in British politics.

Another 1930s trend which Eden helped to foster was the wearing of a pale, often linen, waistcoat with a dark lounge suit. It is, I can say from personal experience, a very pleasing look, though one must be careful and conservative with the choice of shirt and tie. Here Eden pulls it off to perfection:

Again, peaked lapels on the suit, and, of course, a Homburg, worn at a slight angle.

Anthony Eden retained good looks and elegance into late middle age and beyond. By the early 1950s, his reputation was at its height. Foreign Secretary again (for the third time), and Churchill's (often impatient) heir, he brought the Geneva Conference of 1954 to a successful conclusion and was rewarded by HM The Queen with the Order of the Garter. At his second wedding, to Churchill's niece Clarissa, he cut a very dashing figure.

A splendid double-breasted suit, a carnation in the buttonhole, and a flourish of pocket square. Perfect. But he could 'do' casual, too. Observe here the sweater, open-necked shirt and neckerchief, elegant but underplayed, and quite marvellous.

Eden's reputation for style and glamour attracted some criticism. There is a sort of Englishmen who regards care taken over one's appearance with suspicion, and Eden was never short of detractors. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres dismissed him as being "vain as a peacock and [having] all the mannerisms of a petit maître", while Sir Percy Grigg, his Permanent Secretary at the War Office in 1940, described him as a "poor feeble little pansy".

Was Eden vain? My suspicion is not, at least, not in the fully derogatory sense in which the word tends to be used. Certainly, he was careful about his appearance, and was lucky enough to be a first-class clothes horse. He must surely have been conscious of the effect his manner of dress had, and the popularity which it brought him. But my sense is that it was simply second nature to him. It was not an act, in the way in which his successor Harold Macmillan's slight shabbiness and exaggerated old age most definitely was. Of course, it doesn't matter about his intent. The effect is what matters, and the effect was glorious. How many of today's politicians are as glamorous and as renowned for it? Maybe some of them might come across this blog and take a long, hard look at their wardrobes...

No comments:

Post a Comment